Letter of gratitude from Dr. Zalman Grinberg to Captain Jacobson, December 3, 1945

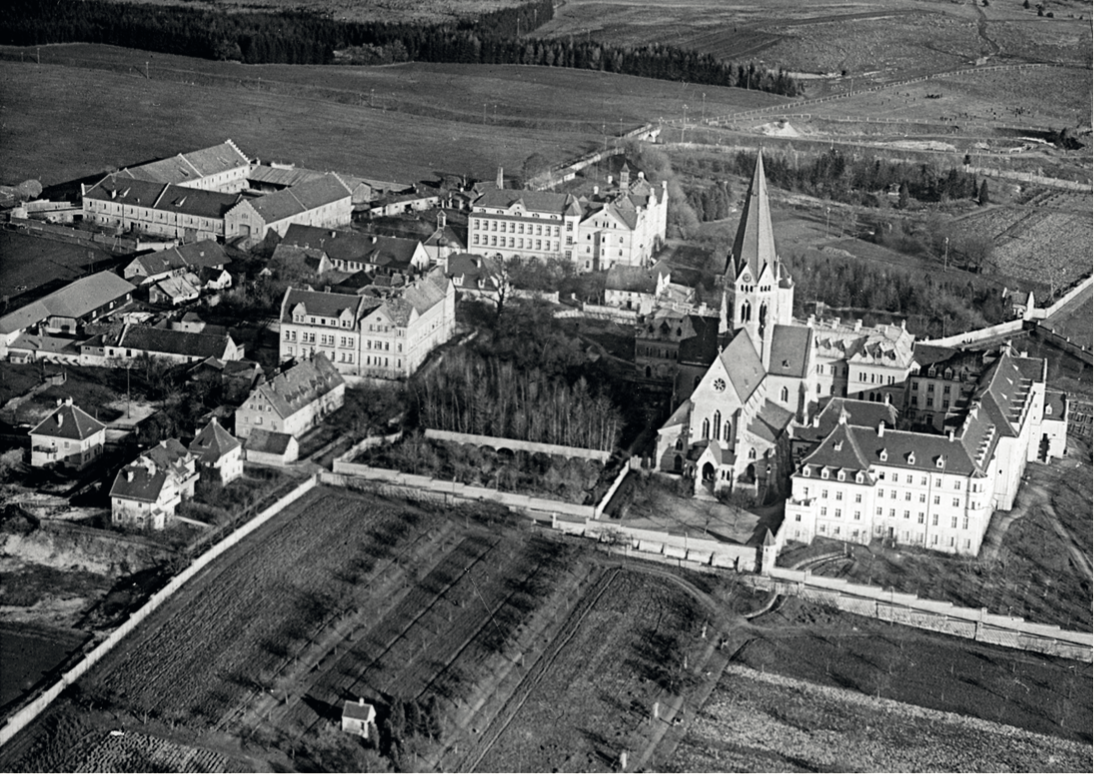

Upon graduation from New York University Dental School in the spring of 1943, my father became a commissioned officer in the United States Army Dental Corp. After basic training in the states, he was shipped to England where he spent the better part of his military career at a British airbase at Duxford, about an hour outside of London, which served as a hub for American bombers and fighter-bombers that bombed Germany during WWII. He worked at the base’s dental clinic, filling and cleaning the teeth of American fighter pilots, navigators, and bombardiers. After Germany surrendered in May 1945, he was shipped again, this time to a German airbase at Kaufbeuren, Bavaria that had been taken over by Allied Forces. He was thus part of the Allied Army of Occupation, although his day to day work remained the same: taking care of the teeth of his fellow servicemen. One day in July 1945, while at the base at Kaufbeuren, he was approached by another American captain in a jeep who offered to show him something. They drove for about 45 minutes to an hour before arriving finally at St. Ottilien. They were greeted by the patients there, many of them still wearing the tattered remains of their concentration camp garb. My dad soon learned that they were survivors of Dachau and had walked to the Abbey after the concentration camp had been liberated by Allied troops. He was appalled by what he saw, especially because more than two months after the surrender of Germany, many of these survivors still did not have adequate clothing, food, toiletries, & etc. Upon returning to his base, he requisitioned supplies to convert a nearby movie theatre into a sanctuary for the holding of services for Jewish servicemen. And from the pulpit of that converted theatre, acting as an unofficial chaplain, he told his comrades about what he had seen at the Abbey and made an urgent plea to them to write to family and friends in the States asking them to send what they could of the items so sorely needed by the survivors of Dachau there. The response was overwhelming. And once a week, every week, over the next several months, my dad gathered up all the packages that had come in over the previous seven days, piled them into a jeep, and drove out to the Abbey where he delivered them to those so in need. He once told me in a proud but not a boastful way that as of his last trip to the Abbey in December 1945 — at which point he was preparing to be shipped home and the international relief effort for “displaced persons” had finally gotten under way — he had personally delivered approximately 5 tons of relief supplies to the victims of Adolph Hitler. It was in recognition of this that Dr. Grinberg wrote the letter in question. And, coincidentally — small world — when Dr. Grinberg emigrated to America, he practiced in the same professional building in Hempstead, New York (Long Island) where my dad had opened up his first dental office after the War. My dad passed away in 2007 when he was 88 years old. He was not a wealthy man. After educating my siblings and me at private universities and professional schools, there was not much left by way of an estate. But he left behind things far more precious: the memory of what had done for the survivors at St. Otillien and the example he had set about what it meant — what it still means — to be a mensch.

Elliott Jacobson

Photograph of Cesia Fromer, nee Szfer, probably in the DP camp Landsberg am Lech 1946 (first woman to the left)

Cesia Fromer (born 1920 in Lodz) was a Holocaust survivor who was liberated from Salzwedel Labor Camp and made her way to Landsberg, DP camp. She married in the DP camp and transferred to the Ottilien hospital in the week of November 8 to 14, 1946 for giving birth to her first child. Due to medical complications she left two weeks later for a hospital in Munich where daughter Rachel was born on December 4th, 1946.

Photographs of Michael Bahat (Bachmat) and Ester Bahat, nee Gamsa, 1946-1948

Ester Bahat stayed in January 1947 in the Maternity Ward of St. Ottilien where she gave birth to her first born son Acharon (Arik) Bahat. Michael Bahat and his wife lived in Munich from 1947 to 1948 close to the headquarter of the Jewish Agency. They worked there as pioneers in the Nocham Zionist youth movement which founded Kibbuzim settlements in Israel. After the emigration to Israel in 1948, Michael Bahat became a renowned educator and a driving force of Jewish-Zionist education, see MichaelBahat_biography. The following photographs give impressions of the training of youngsters who stayed in dispersed Kibbuzim in Germany where they prepared for the emigration to Palestine/Israel. Some photographs go back to the 1930ies. © Information and photographs kindly provided by Arik Bahat, Hod Hasharon.

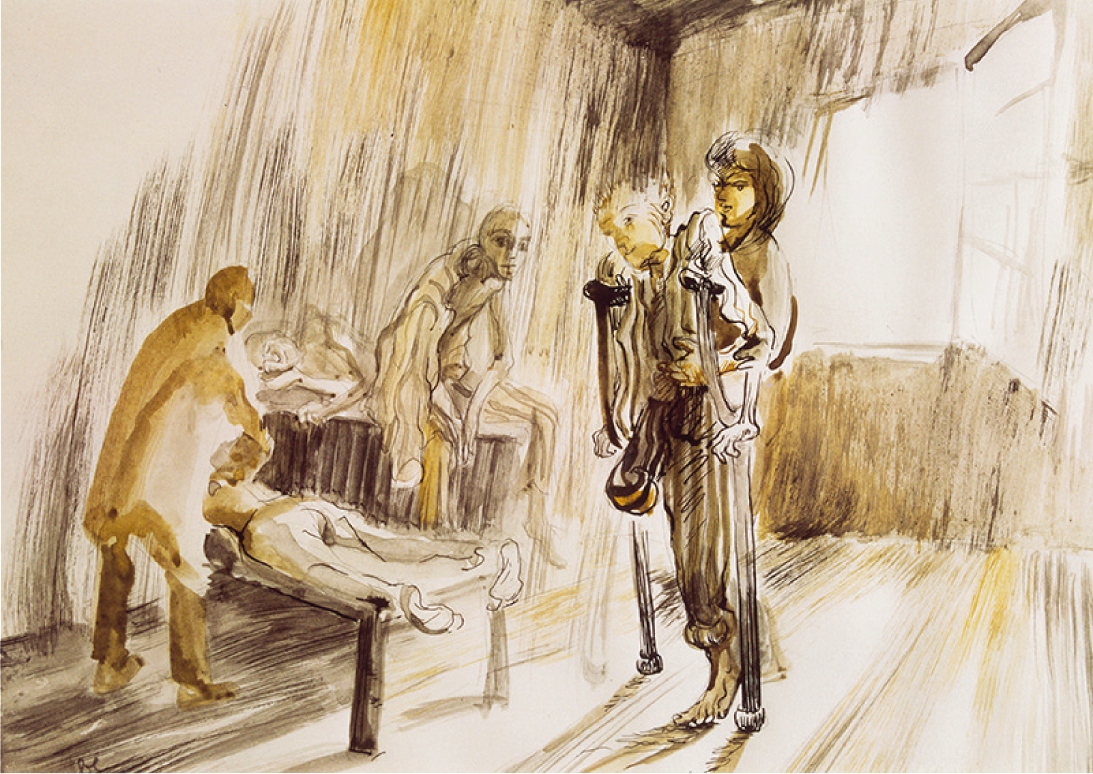

Photographs of Matthew Burger who lived in St. Ottilien from 1946-48

Mates (Matthew) Burger, born August 6, 1923, was at St. Ottilien after a traumatic amputation of his left arm from May 1946 until the dissolution of the hospital in May 5, 1948. He can be seen on a photo of the Jewish Review from May/June 1946. On another photo a nurse can be seen who was very supportive when he was so depressed after the loss of his arm. He had survived the war and the death of his parents and then was devastated by this ironic twist of fate. He also mentioned the surgeon who took great care of him. He met another survivor, Chana Zylbercwajg, at St. Ottilien who become my mother. I was born at Lagerlechfeld in August, 1948. The last person on the right in the group photo (my father not included) might have been a friend of my father’s with the last name of Kurland (Max Burger).

Record of a visit in St. Ottilien by Max Burger in May 2024: Max Burger – A Visit to St. Ottilien

Photographs by courtesy of © Max Burger, New Jersey

David’s story

David Avnir-Steingarten was born in St. Ottilien on June 12, 1947. The family came from Poland and fled after the German invasion to the Russian Zone. After the War, the parents met in Poland where they were part of the Habricha movement which organized the emigration from East European Jews to Palestine through Bavaria. During their time in Munich, their first son, David Avnir, is born in the St. Ottilien Hospital. Report of the family history: Avnir’s story

Moses Groeneman (1905-1977)

My father was in the Kaufering concentration camp, part of Dachau, since July 1944 after his arrest in Lithuania in August 1941. After liberation of the Dachau concentration camp (April/May, 1945), he was transferred to the DP hospital at Sankt Ottilien, where he resided for approximately two years. He is mentioned as resident of the Hospital in Sharit-Haplatah, June 1945. His post-war story involves an extraordinary coincidence. Before the camp was liberated, he was instructed by one of the other inmates (Mischa Aharoni/Moshe Aronowich, who died just weeks before liberation) to contact his brother, Kalman Aharoni in Toledo, Ohio in the U.S., if he ever got out of Kaufering. He was urged to memorize this name and place. When the American army troops liberated the camp (Spring of 1945), one of soldiers, Harry Manson, happened to hear my father repeatedly saying “Kalman Aharoni in Toledo, Ohio.” As it turned out, not only was Mr. Manson from Toledo but he also knew Kalman Aharoni because they were neighbors in Toledo. My father eventually made it to Toledo Ohio, thanks in large part to Mr. Kalman Aharoni, a distant relative, who became his sponsor. But this did not occur until the summer of 1947. In the two years between the time the camp was liberated and he came to the United States, I assume he spent all or most of that time at St. Ottilien. After leaving St. Ottilien, my father came to the U.S. (Toledo, Ohio) in 1947. His American name was revised to become Morris Groeneman. He resumed his work as a master tailor until his death in 1977.

Sid Groeneman, Rockville, Maryland, USA

Photograph by courtesy of © Sid Groeneman, Maryland